Apollo 1

| Apollo 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mission insignia |

|||||

| Mission statistics | |||||

| Mission name | Apollo 1 | ||||

| Command Module | CM-012 | ||||

| Service Module | SM-012 combined mass 45,000 pounds (20,000 kg) |

||||

| Crew size | 3 | ||||

| Booster | Saturn IB SA-204 | ||||

| Launch pad | LC 34 Cape Canaveral Florida, USA |

||||

| Launch date | February 21, 1967 (planned) | ||||

| Mission duration | Up to 14 days (planned) | ||||

| Apogee | 160 nautical miles (300 km) (planned) | ||||

| Perigee | 120 nautical miles (220 km) (planned) | ||||

| Orbital period | ~89.7 minutes (planned) | ||||

| Orbital inclination | ~31° (planned) | ||||

| Crew photo | |||||

|

|||||

| Left to right: Grissom, White, Chaffee | |||||

| Related missions | |||||

|

|||||

|

Italics indicate parameters for the planned mission canceled following the January 27 fire. a The intended recovery carrier was the USS Essex. |

|||||

Apollo 1 (official designation Apollo/Saturn-204) was planned to be the first manned mission of the Apollo manned lunar landing program to launch in February 1967. Its flight was precluded by a fatal fire on January 27, which killed all three crew members (Command Pilot Virgil "Gus" Grissom, Senior Pilot Edward H. White, and Pilot Roger B. Chaffee), and destroyed the Command Module cabin. This occurred during a pre-launch test of the spacecraft on Launch Pad 34 at Cape Canaveral. The name Apollo 1, chosen by the crew, was officially assigned retroactively in commemoration of them.

The Apollo 204 Accident Review Board was promptly formed to determine the cause of the tragedy. Although the ignition source of the fire was never conclusively identified, the astronauts' deaths were attributed to a wide range of lethal design and construction flaws in the early Apollo Command Module. The manned phase of the project was delayed for twenty months while these problems were fixed. The Saturn IB launch vehicle SA-204 (Saturn/Apollo) intended to fly the mission was later used for the first unmanned Lunar Module test flight, Apollo 5.

Contents |

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Command Pilot | Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom | |

| Senior Pilot | Edward H. White II | |

| Pilot | Roger B. Chaffee | |

Backup crews

April - December 1966

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Command Pilot | James McDivitt | |

| Senior Pilot | David Scott | |

| Pilot | Rusty Schweickart | |

| This crew flew on Apollo 9. | ||

December 1966 - January 1967

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Command Pilot | Walter Schirra | |

| Senior Pilot | Donn Eisele | |

| Pilot | Walter Cunningham | |

| This crew flew on Apollo 7. | ||

Mission background

AS-204 was to be the first manned flight of a Command and Service Module (CSM) to Earth orbit, launched on a Saturn 1B. CM-012, the Apollo 1 Command Module, was of an early Block I design before the Lunar Module (LM) landing technique was chosen, and therefore lacked the docking equipment needed for mating to a LM. This would be added to the later Block II design, along with lessons learned to solve technical problems encountered in Block I. At first only two manned Block I missions were planned, but the second one was cancelled in late 1966.

The AS-204 mission was scheduled for February 21, 1967, having already missed a target date for the last quarter of 1966 (it was suggested that the first Apollo flight might coincide with the last Gemini flight, and rendezvous, but this never seems to have been a serious possibility). The flight was to test launch operations, ground tracking and control facilities and the performance of the Apollo-Saturn launch assembly and would have lasted up to two weeks, depending on how the spacecraft performed.[1] Grissom resolved to keep AS-204 in orbit for a full 14 days if there was any way to do so.

AS-204 was intended to be followed by two more Apollo missions in the summer and late autumn of 1967. The first of these would have launched a Block II CSM on a Saturn IB along with an unmanned LM on a second Saturn IB, for a CSM-LM rendezvous and docking in low Earth orbit. The second mission would have launched the CSM and LM together on a Saturn V to high Earth orbit.

Command Module design worries

The Apollo Command Module was much bigger and far more complex than any previously implemented spacecraft design. It was built by North American Aviation, which had originally suggested the hatch open outward and carry explosive bolts in case of emergency. NASA didn't agree, arguing the hatch could accidentally open, as it had on Liberty Bell 7. Before the fire, astronauts successfully lobbied for an outward-opening hatch on future command modules, but NASA subsequently claimed the astronauts were thinking about ease of exit and entry for spacewalks (along with getting out of the CM after splashdown) rather than safety.[2]

North American Aviation had suggested the cabin atmosphere be an oxygen/nitrogen mixture as on the Earth's surface. NASA objected, citing heightened risks such as catastrophic decompression sickness and mismanagement of nitrogen levels, which could cause the astronauts to pass out and die. NASA officials asserted a pure oxygen atmosphere had been used without incident in the Mercury and Gemini programs (which was incorrect: fire and inability to open a door during the fire had been a problem[3]), demonstrating that pure oxygen could be safely employed on Apollo. Also, a pure oxygen design saved weight.

CM-012 was delivered to NASA with 113 significant incomplete planned engineering changes. An additional 623 Engineering Orders were generated subsequent to delivery.[4] The crew expressed serious concerns about fire hazards and other problems (Grissom even famously took a lemon from a tree by his house, telling his wife Betty, "I'm going to hang it on that spacecraft").[5]

In a BBC documentary "NASA: Triumph and Tragedy", Jim McDivitt said that NASA had no idea how 100% oxygen atmosphere would influence burning.[6] Similar remarks by other astronauts were expressed in a documentary "In the Shadow of the Moon."[7]

Incident

Plugs-out test

The January 27, 1967 launch simulation, officially considered not hazardous because the Saturn IB was not loaded with fuel, was a "plugs-out" test to determine whether the spacecraft would operate nominally on internal power while detached from all cables and umbilicals. There was hope that if the spacecraft passed this and subsequent tests, it would be ready to fly on February 21, 1967.[8]

At 1:00 PM (1800 GMT) on January 27 Grissom, White and Chaffee entered the command module fully suited, were strapped into their seats and hooked up to the spacecraft's systems in preparation for the plugs-out test. There were immediate problems. A sour "buttermilk" smell in the air circulating through Grissom's suit delayed the launch simulation until 2:42 PM. Three minutes later the hatch was sealed and high-pressure pure oxygen began replacing the air in the cabin.

Further problems included episodes of high oxygen flow apparently linked to movements by the astronauts in their flightsuits. There were also faulty communications between the crew, the control room, the operations and checkout building and the complex 34 blockhouse. "How are we going to get to the Moon if we can't talk between three buildings?" Grissom complained in frustration over the communication loop. This put the launch simulation on hold again at 5:40. Most countdown functions had been successfully completed by 6:20 but the countdown was still holding at T minus 10 minutes at 6:30 with all cables and umbilicals still attached to the command module while attempts were made to fix the communication problem.

Fire

The crew members were reclining in their horizontal couches, running through a checklist when a voltage transient was recorded at 6:30:54 (23:30:54 GMT). Ten seconds later (at 6:31:04) Chaffee said, "Hey..." Scuffling sounds followed for three seconds before Grissom shouted "Fire!" Chaffee then reported, "We've got a fire in the cockpit," and White said "Fire in the cockpit!" After nearly ten seconds of frenetic movement noises Chaffee yelled, "We've got a bad fire! Let's get out! We're burning up! We're on fire!"[9] Some witnesses said they saw Ed White on the television monitors, reaching for the hatch release handle as flames in the cabin spread from left to right and licked the window. Only 17 seconds after the first indication by crew of any fire, the transmission ended abruptly at 6:31:21 with a scream of pain as the cabin ruptured after rapidly expanding gases from the fire overpressurized the CM to 29 psi (200 kPa).[10]

Intense heat, dense toxic smoke, malfunctioning gas masks and shock waves and explosions from the cabin hampered the ground crew's rescue efforts. There were fears the fire might ignite the solid fuel rockets in the launch escape tower above the command module, likely killing nearby ground personnel. It took five minutes to open the inner and outer hatches, a set of three with many ratchets. By this time the fire in the command module had gone out. Although the cabin lights remained lit the ground crew was at first unable to find the astronauts. As the smoke cleared they found the bodies but were not able to remove them. The fire had partly melted the astronauts' nylon space suits and the hoses connecting them to the life support system. Grissom's body was found lying mostly on the deck. His and White's suits were fused together. The body of Ed White (whom mission protocol had tasked with opening the hatch) was lying back in his center couch. White would not have been able to open the inward-opening hatch against the internal pressure. Chaffee's job was to shut down the spacecraft systems and maintain communications with ground control. His body was still strapped into the right-hand seat.

Aftermath

According to the Apollo 204 Review Board, Grissom suffered severe third degree burns on over a third of his body and his spacesuit was mostly destroyed. White suffered third degree burns on almost half of his body and a quarter of his spacesuit had melted away. Chaffee suffered third degree burns over almost a quarter of his body and a small portion of his spacesuit was damaged. It was later confirmed the crew had died of smoke inhalation with burns contributing.[11] In later lawsuits brought by Gus Grissom's widow Betty Grissom there were claims the astronauts had lived longer than NASA claimed publicly.[12]

The review board found the documentation for CM-012 so lacking that they were at times unable to determine what had been installed in the spacecraft or what was in it at the time of the accident.

Cause

Since the CM was designed to endure outward pressure in the vacuum of space, the plugs-out test had been run with the cabin pressure at over 16 psi, almost 2 psi above the ambient sea level pressure at Launch Complex 34 and near the upper limits of measuring devices in the spacecraft. This represented over 5 times the oxygen density carried within the Mercury and Gemini spacecraft while in spaceflight (which was only 3 psi but equal to the partial pressure of oxygen at sea level and thus very breathable). Following a worldwide survey of artificial oxygen-rich environments, it was found that rarely if ever had a 100% oxygen environment been created and maintained at such a high pressure, in which materials not normally considered highly flammable can burst into flame. The investigation also found much substandard wiring and plumbing in the craft. Hence, the fire was at first believed to have been caused by a spark somewhere in the over 25 km (16 mi) of wiring threaded throughout the command module.

The review board noted a silver-plated copper wire running through an environmental control unit near the center couch had become stripped of its Teflon insulation and abraded by repeated opening and closing of a small access door. This weak point in the wiring also ran near a junction in an ethylene glycol/water cooling line which was known to be prone to leaks. The electrolysis of ethylene glycol solution with the silver anode was a notable hazard which could cause a violent exothermic reaction, igniting the ethylene glycol mixture in the CM's corrosive test atmosphere of pure, high-pressure oxygen.[13][14]

The panel cited how the NASA crew systems department had installed 34 square feet (3.2 m2) of fuzzy Velcro throughout the spacecraft, almost like carpeting. This Velcro was found to be explosive in a high-pressure 100% oxygen environment. Up to 70 pounds of other non-metallic flammable materials had crept into the design. Buzz Aldrin in Men From Earth states that the three astronauts complained that they wanted the flammable material removed, and that there was to be no flammable material in the spacecraft; the flammable material was removed, but was replaced prior to delivery to Cape Kennedy.

In 1968 a team of MIT physicists went to Cape Kennedy and performed a static discharge test in the CM-103 command module while it was being prepared for the launch of Apollo 8. With an electroscope, they measured the approximate energy of static discharges caused by a test crew dressed in nylon flight pressure suits and reclining on the nylon flight seats. The MIT investigators found sufficient energy for ignition discharged repeatedly when crew-members shifted in their seats and then touched the spacecraft's aluminum panels.

However, the ignition source for the Apollo 1 fire was never officially determined.[11]

Command Module redesign

After the fire the Apollo project was grounded for review and re-design. In hindsight the Command Module was understood to be extremely hazardous and in some instances, carelessly assembled (A misplaced socket wrench was even found in the cabin). Many design changes were made:

- The cabin atmosphere at launch was changed to 60% O2 and 40% N2 at sea-level pressure (14.7 psi or 1013 millibars). During ascent the cabin rapidly vented down to 5 psi (345 mbar), releasing approximately 2/3 of the N2 (and O2) originally present at launch. The vent then closed and the environmental control system maintained a nominal cabin pressure of 5 psi as the spacecraft continued into vacuum. The cabin was then very slowly purged (vented to space and simultaneously replaced with 100% O2) so the N2 concentration fell asymptotically to zero over the next day. Although the new cabin launch atmosphere was significantly safer than 100% O2, it was still more hazardous than ordinary sea level air with only 21% O2. This was necessary to ensure a sufficient partial pressure of oxygen when the astronauts removed their helmets shortly after launch. (60% of the nominal 5 psi cabin pressure is 3 psi; the partial pressure of oxygen in sea-level air is 20.9% of 14.7 psi or 3.07 psi.)

- The environment within the astronauts' pressure suits was not changed. Because of the rapid drop in cabin (and suit) pressures during ascent, decompression sickness was likely unless the N2 had been purged from the astronauts' tissues prior to launch. They would still breathe pure O2 starting several hours before launch and continuing until orbital insertion. Avoiding the "bends" was considered worth the residual risk of an oxygen-accelerated fire within a suit.

- The hatch was completely redesigned to open outward (which had already been planned) in less than ten seconds. It used a cartridge of pressurized nitrogen to drive the release mechanism in an emergency, as opposed to the pyrotechnic bolts used on Mercury.

- Flammable materials in the cabin were replaced with self-extinguishing versions.

- Plumbing and wiring were covered with protective insulation.

- 1,407 wiring problems were corrected.

- Nylon suits (seen in the crew portrait above) were replaced with suits made of early Beta cloth, a non-flammable, highly melt-resistant fabric woven from fiberglass and coated with Teflon.

Thorough protocols were implemented for documenting spacecraft construction and maintenance. By all accounts the design changes were successful and justified the 21-month delay of the first manned mission, Apollo 7.

Previous incidents

In March 1961 Soviet cosmonaut Valentin Bondarenko had died after a fire in a high-oxygen isolation chamber.[15] The USSR concealed the tragedy for over 20 years, which subsequently caused some speculation as to whether or not the Apollo 1 disaster might have been averted had NASA been aware of the incident.[16] However, the fire hazards of a 100%-oxygen sea-level pressure environment had been well described by 1967 and many deaths from flash fires had been publicly reported during the 1950s and 1960s. A 1966 editorial in the journal Space/Aeronautics asserted "The odds are that the first spaceflight casualty due to environmental exposure will occur not in space, but on the ground", and further noted that safety protocols for the Apollo project were thoroughly lacking.[2]

Other warnings on this hazard predating the fatal incident include these US reports, including one directly from NASA in Houston:[17]

- - Selection of Space Cabin Atmospheres. Part II: Fire and Blast Hazaards [sic] in Space Cabins. (Emanuel M. Roth; Dept of Aeronautics Medicine and Bioastronautics, Lovelace Foundation for Medical Education and Research. c.1964-1966.)

- - "Fire Prevention in Manned Spacecraft and Test Chamber Oxygen Atmospheres." (MSC. NASA General Working Paper 10 063. October 10, 1966)

Scapegoats

Committees in both houses of the US Congress with oversight of the space program soon launched their own investigations, including the Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, chaired by Senator Clinton P. Anderson. In the course of Sen. Anderson's hearings, the existence of a memorandum written in late 1965, just over one year before the accident, was disclosed. This was written by Apollo Program Director Lt Gen Samuel C. Phillips to Lee Atwood (president of North American Aviation, prime contractor on the CSM), detailing complaints of inadequate quality, schedule delays, and cost overruns. This document became known as "the Phillips Report", despite Phillips' refusal to characterize it as such before Congress.[18]

NASA Administrator James E. Webb was also called before the committee and testified he was unaware of such a "report". A minor controversy then arose, because Phillips had used the phrase "this report" in the document's cover memo. Phillips and Webb were not lying, because in NASA parlance a "report" was considered an official public document (such as the 204 Review Board's Report), whereas Phillip's document was considered an internal communication between NASA and a contractor. Nevertheless, some Congressmen were angered by what they perceived as Webb's deception (and not being informed of the issues at the time), and questioned NASA's selection of North American as prime contractor. On May 11, Webb issued a statement defending the selection. On June 9, Deputy Administrator Dr. Robert C. Seamans, Jr. filed a seven-page memorandum documenting the process that led to North American's selection in November 1961.[19]

The potential political threat to Apollo blew over, due in large part to the support of President Lyndon Johnson, who at the time still wielded a measure of influence with the Congress from his own Senatorial experience. He was a staunch supporter of NASA since its inception, had even recommended the Moon program to President John F. Kennedy in 1961, and was skilled at portraying it as part of Kennedy's legacy.

But internal acrimony developed between NASA and North American over assignment of blame. North American argued unsuccessfully that it was not responsible for the fatal error in spacecraft atmosphere design. Finally, Webb contacted Atwood, and demanded that either he or Chief Engineer Harrison "Stormy" Storms resign. Atwood elected to fire Storms.[20]

On the NASA side, Joe Shea, manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office, became unfit for duty in the aftermath and was removed from his position, although not fired.[21]

Mission insignia

The Apollo 1 insignia has a center showing a Command/Service Module flying over the southeastern United States with Florida (the launch point) prominent. The Moon is seen in the distance, symbolic of the eventual program goal. A yellow border carries the mission and astronaut names with another border set with stars and stripes, trimmed in gold. The insignia was designed by the crew, with the artwork done by Allen Stevens of Rockwell International.[22] [23]

Memorials

Gus Grissom and Roger Chaffee were buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Ed White was buried at the cemetery of the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York. Their names are also enshrined on the Space Mirror Memorial at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in Merritt Island, Florida.

An Apollo 1 mission patch was left on the Moon's surface during the first manned lunar landing by Apollo 11.

Launch Complex 34

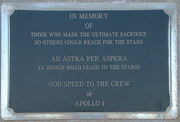

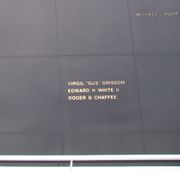

After the Apollo 1 fire, Launch Complex 34 was subsequently used only for the launch of Apollo 7 and later dismantled but the launch platform remains at the site () along with a few other concrete and steel-reinforced structures. The launch platform bears two plaques noting the tragedy.

One reads: LAUNCH COMPLEX 34, Friday, 27 January 1967, 1831 Hours. Dedicated to the living memory of the crew of the Apollo 1: USAF. Lt. Colonel Virgil I. Grissom, USAF. Lt. Colonel Edward H. White, II, U.S.N. Lt. Commander Roger B. Chaffee. They gave their lives in service to their country in the ongoing exploration of humankind's final frontier. Remember them not for how they died but for those ideals for which they lived.

The other reads: In memory of those who made the ultimate sacrifice so others could reach for the stars; Ad astra per aspera (a rough road leads to the stars); God speed to the crew of Apollo 1

In January 2005 three granite benches built by a college classmate of one of the astronauts, one for each member of the crew, were installed at the site on the southern edge of the launch pad. The benches bear the names of the astronauts and the military insignias of the services they represented. Each year the families of the Apollo 1 crew are invited to the site for a memorial, and the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Center offers a visit to the site for those who choose to take a special tour of the historic launch sites on Cape Canaveral.

Launch platform at LC-34 with Apollo 1 dedication plaque visible on rear of right post |

Dedication plaque attached to launch platform at LC-34 |

Memorial plaque attached to launch platform at LC-34 |

Marble memorial benches on the southern edge of the launch pad |

Memorial kiosk at Pad 34 |

Stars, landmarks on the Moon and Mars

- Apollo astronauts frequently aligned their spacecraft inertial navigation platforms and determined their positions relative to the Earth and Moon by sighting sets of stars with optical instruments. As a practical joke, the Apollo 1 crew named three of the stars in the Apollo catalog after themselves and introduced them into NASA documentation. Gamma Cassiopeiae became Navi -- Ivan, Gus Grissom's middle name spelled backwards (also short for "Navigation"). Iota Ursae Majoris became Dnoces -- "Second" spelled backwards, for Edward H. White II. And Gamma Velorum became Regor -- Roger (Chaffee) spelled backwards. These names quickly stuck after the Apollo 1 accident and were regularly used by later Apollo crews.[24]

- Craters on the Moon and hills on Mars are named after the three Apollo 1 astronauts.

Naming of Apollo 1

When North American Aviation shipped spacecraft CM-012 to Kennedy Space Center it bore a banner proclaiming it as Apollo One. Grissom's crew had received approval for an Apollo 1 patch in June 1966 but NASA was planning to call the mission "AS-204." After the fire, the astronauts' widows asked that Apollo 1 be reserved for the flight their husbands never made.

Apollo 1's (AS-204) Saturn IB rocket was taken down from Launch Complex 34, later reassembled at Launch Complex 37B and used to launch the Apollo 5 LM-1 into Earth orbit for the first Lunar Module test mission.

Effect on early Apollo mission names

For a time mission planners called the next scheduled launch Apollo 2. There were also suggestions the first Apollo CSM flights be named wholly out of chronological sequence as Apollo 1 (AS-204), Apollo 1A (AS-201), Apollo 2 (AS-202) and Apollo 3 (AS-203) but the NASA project designation committee decided on Apollo 4 for the first (unmanned) Apollo-Saturn V mission (AS-501), with no retroactive renaming of earlier missions. Hence, AS-203 is now sometimes informally (and chronologically) referred to as Apollo 2 and likewise, AS-202 as Apollo 3.

Civic and other memorials

- Grissom Hall, student residence hall at the Florida Institute of Technology.

- Three public schools in Huntsville, Alabama (home of George C. Marshall Space Flight Center and the United States Space & Rocket Center): Virgil I. Grissom High School,[25] Ed White Middle School,[26] and Roger B. Chaffee Elementary.[27]

- Edward White Middle School in White's hometown of San Antonio, Texas.[28]

- Edward H. White II High School in Jacksonville, Florida.[29]

- Edward H. White II Elementary School, El Lago, Texas.[30]

- Edward H. White II Memorial Youth Center, Seabrook, Texas.[31]

- Virgil Grissom Elementary School in Tulsa, Oklahoma.[32]

- Roger B. Chaffee Elementary School at NAS Bermuda (closed)

- Virgil I. Grissom Middle School at Warren, Michigan

- Virgil I. Grissom Middle School in Mishawaka, Indiana, part of the Penn-Harris-Madison School Corporation

- A memorial to Grissom in Spring Mill State Park, near his hometown of Mitchell, Indiana. In Mitchell itself is the town's Gus Grissom Memorial. Mitchell High School's auditorium is also named for him.

- Three man-made oil drilling islands in the harbor off Long Beach, California are named Grissom, White and Chaffee. A fourth island is named for Theodore Freeman,[33][34] an Air Force test pilot chosen as an astronaut in 1963 but who was killed while piloting a T-38 jet when it crashed at Ellington AFB.

- A road that formerly ran through Kent County International Airport (GRR) in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Chaffee's hometown, was named Roger B. Chaffee Memorial Boulevard after the airport was moved further from the city limits.

- The Roger B. Chaffee Planetarium is located at the Grand Rapids Public Museum.[35]

- White Hall and Grissom Hall at Chanute Air Force Base (closed, 1993), Rantoul, Illinois.

- The names of Grissom, White and Chaffee were used for streets in Amherst, NY. These are connected to Niagara Falls Boulevard and located near the Bell plant, where the X planes were built in the 1940s. There is a museum dedicated to the work of Bell in the aeronautic sciences. The roads commemorating White and Chaffee are still in existence, however a local restaurant purchased the entire length of Grissom Drive, and renamed it against the protests of the local citizenry and the town board.

- Three adjacent parks in Fullerton, California are each named for Grissom, Chaffee and White. The parks are located near a former Hughes Aircraft research and development facility. A Hughes subsidiary, Hughes Space and Communications Company, built components for Project Apollo.[36]

- Grissom Joint Air Force Reserve Base (formerly Grissom Air Force Base, formerly Bunker Hill AFB, 65 miles (105 km) north of Indianapolis) in Grissom's home state of Indiana was renamed for Grissom on May 12, 1968.

- The three letter identifier of the VOR located at Grissom ARB is GUS, Grissom's nickname

- Two buildings on the campus of Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana are named for Grissom and Chaffee (both Purdue alumni). Grissom Hall houses the School of Industrial Engineering (and was home to the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics before it moved into the new Neil Armstrong Hall of Engineering). Chaffee Hall is the administration complex of Maurice J. Zucrow Laboratories where thermal sciences and rocket propulsion are studied.

- Grissom Parkway runs between Cocoa and Titusville, Florida, intersecting White Drive and Chaffee Drive near the Titusville Police Department.

- Virgil I. Grissom Library in Newport News, Virginia.

- Virgil I. Grissom Bridge across the Hampton River, on Rt 258 (Mercury Blvd, named after the Mercury program) in Hampton, VA, is one of the six bridges and one road named after the original 7 Mercury astronauts, who trained in the area.

Remains of CM-012

The Apollo 1 command module has never been on public display. After the accident the burned-out spacecraft was removed and taken to Kennedy Space Center to be studied for any information that might prevent a recurrence of the tragedy. It was then moved to the NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia and placed in a secured storage warehouse. On February 17, 2007 the wreckage of CM-012 was moved approximately 100 feet (30 m) to a newer, environmentally-controlled warehouse.[37] Only a few weeks earlier Gus Grissom's brother Lowell publicly suggested CM-012 be permanently entombed in the concrete remains of Launch Complex 34.[38]

Popular culture

- An episode of the HBO miniseries From the Earth to the Moon tells the story of the Apollo 1 tragedy and its aftermath. It stars Mark Rolston as Gus Grissom, Chris Isaak as Ed White and Ben Marley as Roger Chaffee.

- The accident is briefly depicted in the opening scene of the film Apollo 13.

- The memorial plaque is briefly depicted in a scene from the movie Armageddon.

- The movie Star Trek III: The Search For Spock features a science vessel named the USS Grissom. Also, the TV series Star Trek: Deep Space Nine features a shuttlecraft named the Chaffee.

- Grissom, White, and Chaffee are mentioned in the song "Rockin’ At The Tea Dance" by the Kansas City, Missouri band The Rainmakers.

See also

- Apollo program

- Space accidents and incidents

- Joseph Francis Shea

- List of unusual deaths

References

Notes

- ↑ Benson 1978: Chapter 18-1 - The Fire That Seared The Spaceport, "Introduction"

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Benson 1978: Chapter 18-2 - The Fire That Seared The Spaceport, "Predictions of Trouble"

- ↑ Colonel B. Dean Smith (2006). The Fire That NASA Never Had. PublishAmerica. ISBN 978-1424125746.

- ↑ Report of Apollo 204 Review Board

- ↑ Mary C., White. "Gus Grissom". Detailed Biographies of Apollo I Crew. NASA History. http://history.nasa.gov/Apollo204/zorn/grissom.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1466415/

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0925248

- ↑ "Apollo 1: The Fire 27 January 1967". NASA Special Publication-4029. http://history.nasa.gov/SP-4029/Apollo_01a_Summary.htm.

- ↑ "Apollo 1 Fire Timeline". NASA Special Publication-4029. NASA History. http://history.nasa.gov/SP-4029/Apollo_01c_Timeline.htm.

- ↑ Seamans, Robert C., Jr. (1967-04-05). "Memorandum". Report of Apollo 204 Review Board. NASA History Office. http://www.hq.nasa.gov/pao/History/Apollo204/seamans.html.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Seamans, Robert C., Jr. (1967-04-05). "Findings, Determinations And Recommendations". Report of Apollo 204 Review Board. NASA History Office. http://www.hq.nasa.gov/pao/History/Apollo204/find.html. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ↑ See Dennis E. Powell, "Obviously, A Major Malfunction" Miami [Fla.] Herald Sunday magazine, November 13, 1988.

- ↑ "NASA history SP-4009". http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4009/v4p2b.htm.

- ↑ In 1967 a vice president of North American Aviation, John McCarthy, speculated that Grissom had accidentally "scuffed the insulation of a wire" whilst moving about the spacecraft but his remarks were ignored by the review board and strongly rejected by a congressional committee. Frank Borman, who had been the first astronaut to go inside the burned spacecraft, testified, "We found no evidence to support the thesis that Gus, or any of the crew members kicked the wire that ignited the flammables." A 1978 history of the accident written internally by NASA said at the time, "the spark that led to the fire still has wide currency at Kennedy Space Center. Men differ, however, on the cause of the scuff." (Benson 1978: Chapter 18-6 - The Fire That Seared The Spaceport, "The Review Board", retrieved May 12, 2008) Soon after making his comment McCarthy had said, "I only brought it up as a hypothesis." ("Blind Spot". Time Magazine. 1967-04-21. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,843575-2,00.html. Retrieved 2008-05-21.)

- ↑ Sputnik and the Soviet Space Challenge, Asif Siddiqi, page 266, ISBN 0-8130-2627-X

- ↑ Charles, John (2007-01-29). "Could the CIA have prevented the Apollo 1 fire?". The Space Review. http://www.thespacereview.com/article/797/1. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ↑ "Bellcomm, Inc Technical Library Collection". National Air and Space Museum, Archives Division. 2001. http://www.nasm.si.edu/research/arch/findaids/bellcomm/bci_print.html. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ↑ Garber, Steve (February 3, 2003). "NASA Apollo Mission Apollo-1 -- Phillips Report". NASA History Office. http://history.nasa.gov/Apollo204/phillip1.html. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- ↑ "CSM Source Selection". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/craft/csmction.htm.

- ↑ Storms interview with historian James Burke for BBC television "The Other Side of the Moon." May 18, 1979

- ↑ Murray, Charles, & Cox, Catherine. Apollo: The Race to the Moon (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1989), pp.pp. 213–14.

- ↑ Dorr, Eugene. "Space Mission Patches - Apollo 1 Patch". http://genedorr.com/patches/Apollo/Ap01.html. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ Hengeveld, Ed. "The man behind the Moon mission patches". collectSPACE. http://www.collectspace.com/news/news-052008a.html. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ "Post-landing Activities". Apollo 15 Lunar Surface Journal. 2006-01-15. http://www.hq.nasa.gov/alsj/a15/a15.postland.html. Retrieved 2007-07-26. Section 105:11:33.

- ↑ "Virgil I. Grissom High School". Huntsville City Schools. http://www.hsv.k12.al.us/schools/high/ghs/. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ↑ "Ed White MIddle School". Huntsville City Schools. http://www.hsv.k12.al.us/schools/middle/ewms/index_new.html. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ↑ "Roger B. Chaffee Elementary School". Huntsville City Schools. http://www.hsv.k12.al.us/schools/elementary/chafes/. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ↑ "Edward H. White Middle School". North East Independent School District - San Antonio, Texas. http://www.neisd.net/white/. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ↑ "Edward H. White High School". Duval County Public Schools. http://www.duvalschools.org/edwhite/. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ↑ "Edward H. White Elementary". Duval County Public Schools. http://www.ccisd.net/school/white.html. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ↑ "Ed White Memorial Youth Center". Ed White Memorial Youth Center. http://stall.net/ewmyc/. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ↑ "Grissom Elementary School". Tulsa Public Schools. http://www.tulsaschools.org/schools/grissom/. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ↑ Fallen Astronaut

- ↑ pdf of City of Long Beach Economic Zones

- ↑ "Roger B. Chaffee Planetarium". Grand Rapids Public Museum. http://www.grmuseum.org/planetarium. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ↑ "Chaffee Park, Rosecrans Avenue, Fullerton, CA - Google Maps". Maps.google.com. 1970-01-01. http://maps.google.com/maps?f=q&source=s_q&hl=en&geocode=&q=Chaffee+Park,+Rosecrans+Avenue,+Fullerton,+CA&sll=37.0625,-95.677068&sspn=28.529345,54.052734&ie=UTF8&hq=Chaffee+Park,&hnear=Rosecrans+Ave,+Fullerton,+CA&ll=33.898276,-117.950506&spn=0.029138,0.052786&z=14. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- ↑ Weil, Martin (2007-02-18). "Ill-Fated Apollo 1 Capsule Moved to New Site". The Washington Post: p. C5.

- ↑ "Apollo 1 astronauts honored at Cape". Palm Beach Post. 2007-01-27. http://www.palmbeachpost.com/state/content/state/epaper/2007/01/27/0127apollo.html. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

Bibliography

- Benson, Charles D.; William Barnaby Faherty (1978). Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities and Operations. NASA History Series. NASA Special Publication-4204. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4204/contents.html.

- Bergaust, Eric (1968). Murder on Pad 34. Puntam Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0399105630..

- Lattimer, Dick (1985). All We Did was Fly to the Moon. Whispering Eagle Press. ISBN 0-9611228-0-3.

External links

- NASA Apollo 1 website Official website

- Baron testimony at investigation before Olin Teague, 21. April 1967

- Apollo 204 Review Board Final Report, NASA's final report on its investigation, April 5, 1967

- Apollo 204 Accident: Report of the Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, United States Senate, with Additional Views, Final report of the U.S. Senate investigation, January 30, 1968

- Apollo 1 Crew- U.S. Spaceflight History Biography

- Apollo Operations Handbook, Command and Service Module, Spacecraft 012 (The flight manual for CSM 012)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||